The Columbo Conundrum

Lieutenant Columbo is a working class agent of justice against the rich and powerful and arrogant. Just one more thing — he’s also a cop.

Toward the end of the 1972 Columbo episode “The Greenhouse Jungle,” orchid fancier Jarvis Goodland strides within his house with a sense of triumph. Jarvis started the episode convincing his monied but moronic nephew Tony (Bradford Dillard) to fake a kidnapping as a way to punish the lad’s unfaithful wife Cathy (Sandra Smith). Once Cathy delivered the cash, Jarvis killed Tony and took the money. Even better, Jarvis managed to pin the murder on Cathy, thanks to the way he manipulated eager LAPD sergeant Frederic Wilson (Bob Dishy).

Just one thing puts a damper on Jarvis’s day of victory: the disheveled detective he finds sitting in his greenhouse at 3 am.

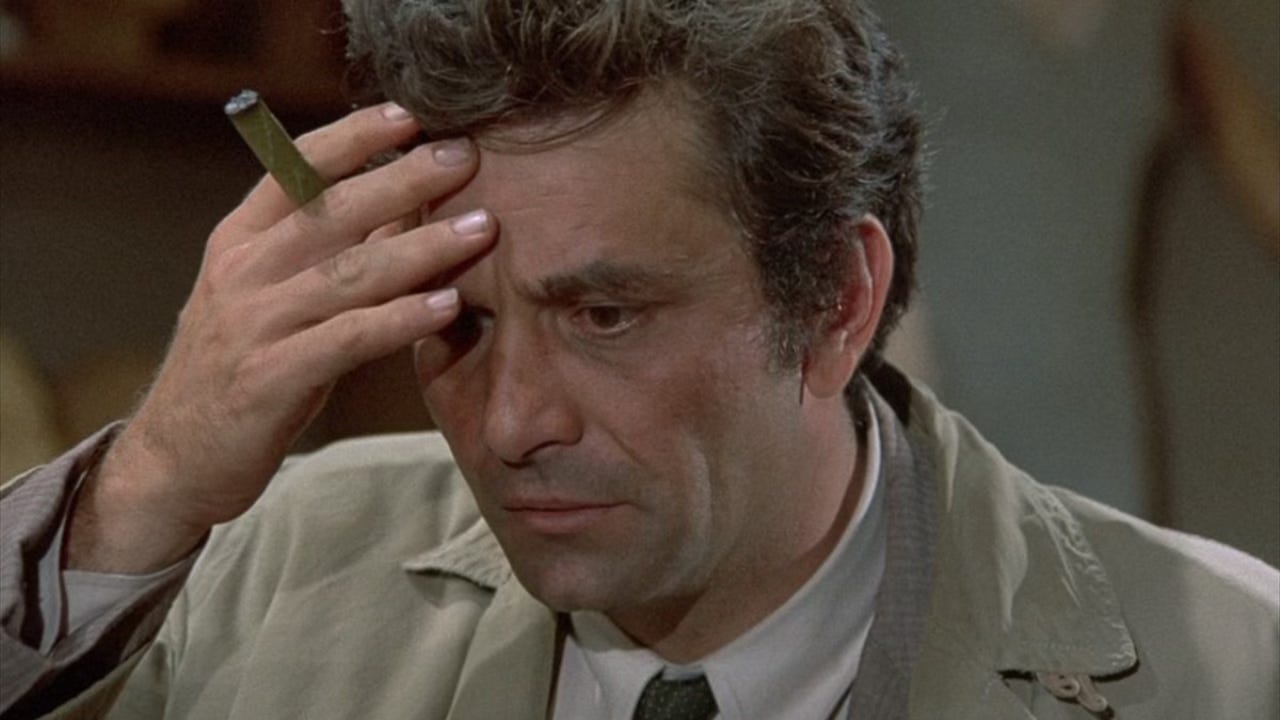

“What the devil are you doing here,” demands Jarvis (Ray Milland), in the same condescending tone he uses with everyone. But it doesn’t bother Lieutenant Columbo, in his signature brown raincoat and omnipresent cigar.

Instead, Columbo talks about his newfound respect for horticulture, even when Sgt. Wilson arrives with Cathy in tow, showing concern for the latter’s comfort but nothing else. That is, until another officer delivers analysis from headquarters. Columbo starts to explain the facts of the case, ignoring Jarvis’s insults until he gets to the point.

Looking at Jarvis, Columbo declares, “Mr. Goodwin, I just don’t know how you’re gonna explain this.” For all of his plotting and planning, Jarvis failed to explain how the gun that he used to shoot at a burglar a year prior was also used to kill Tony and also found in Cathy’s bedroom earlier in the evening.

Milland lets the embarrassment at being bested by Columbo wash over the face of Jarvis. Jarvis finds no words to explain himself, but we viewers cheer, especially since “The Greenhouse Jungle” closes with the lieutenant planning on talking to his wife Mrs. Columbo, one of the show’s most beloved ongoing bits.

Like most episodes of Columbo, “The Greenhouse Jungle” still thrills viewers today, even viewers who understand the dangers of copaganda. That thrill isn’t a condemnation against the viewers or even the show. Rather, it’s a condemnation of pop culture’s inability to think of concepts such as justice and equality outside of a police context.

This Old Man

Created by Richard Levinson and William Link and played by the craggy but captivating Peter Falk, Columbo appeared in 69 movie length episodes, aired on NBC and ABC between 1968 and 2003. Massively popular in its own time, Columbo recently found a whole new set of younger fans, and not just because Kino Lorber released a handsome set of blu-ray remasters.

Columbo caught on in the pandemic for a variety of reasons. In an age of serialized storytelling that stretch a singe plot across one over-padded seasons, the show’s standalone tales offered contained pleasures, episodes with a beginning, middle, and end. Outstanding guest stars played murderers who matched wits with Columbo, including Star Trek alums William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy, New Hollywood power couple John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands, Matthew Rhys (a decade before The Americans), and even Johnny Cash.

All of these famous faces shared the screen with Falk, an actor unlike any star we’ve seen before or since. With his trademark squint, a product of the glass eye he’s had since childhood, and his 12-pack-a-day voice, Falk played Columbo like your best friend’s grandpa, even when he was only in his 40s. The show embraced the types of running gags that modern series find passé, including references to his wife (never actually scene, but portrayed by none other than Kate Mulgrew in the much-hated, and Falk-less, spin-off series Mrs. Columbo), interactions with his Bassett Hound called Dog, and his catch phrase, “Just one more thing…”

Best of all, most Columbo episodes pit the lieutenant against the rich and powerful. In 1971’s "Murder by the Book,” written by a pre-NYPD Blue Stephen Bochco and directed by a pre-The Sugarland Express Steven Spielberg, Columbo ensnares a successful novelist who killed his writing partner. In 1973’s “Lovely But Lethal,” a perfume magnate (Vera Miles) kills her chief scientist (Martin Sheen) to keep pace with her rival (Vincent Price), only to be undone by Columbo. The lieutenant leaves a right-wing radio host (Shatner) speechless in 1994’s “Butterfly in Shades of Gray” (directed by frequent Adam Sandler collaborator Dennis Dugan) and a blustering jeweler (Rip Torn) in 1991’s “Death Hits the Jackpot.”

Against these extravagant baddies, the show constantly reminded viewers that Columbo was poor and working class. “The Greenhouse Jungle” introduces a gag repeated throughout the series, in which a uniformed officer sees Columbo’s beat-up Peugeot 403 automobile and assumes he’s a bum come to gawk. They continue harassing Columbo until he shows his badge, proving that he is a cop.

More than just good-natured jabs at the lieutenant’s appearance, this running gag sets Columbo apart from other TV cops. He’s not the all-business Joe Friday of Dragnet nor the cool and tough Kojak and certainly not his later competitors Elliot Stabler and Olivia Benson of Law & Order: SVU. Columbo opened the door for slovenly types like NYPD Blue’s Andrew Sipowicz or The Wire’s perpetual pain-in-the-butt Jimmy McNulty, but he never indulged in the violence that made those guys so compelling. In fact, in the 1975 standout “The Forgotten Lady,” Columbo spends half the episode dodging administrators who reprimand him for neglecting his firearm.

Columbo looks unlike any other cop we’ve seen, either in real-life or on television. And that’s exactly the problem.

Columbo and the Class Consciousness

“The Greenhouse Jungle” killer Jarvis Goodland is among the most unlikable antagonists in Columbo history. But he’s right to be annoyed to find the lieutenant sitting in his greenhouse at three in the morning. After all, Columbo has produced no warrant, and is thus trespassing. In fact, warrantless trespassing and surveillance happens regularly in Columbo, with the detective often walking into houses, checking out lawns, and even recording suspects without following the law.

Columbo does produce a warrant to search the property of high-powered lawyer Hugh Creighton (Dabney Coleman) in 1991’s “Columbo and the Murder of a Rock Star,” but the episode ends with the lieutenant fumbling as he reads the accused his Miranda rights. 1995’s “Strange Bedfellows” finds Columbo teaming with mobster Vincenzo Fortelli (Rod Steiger) to catch murderous ranch owner Graham McVeigh (George Wendt), and even recommends that the accused not seek an attorney, as Fortelli would retaliate. And that doesn’t even include all the ridiculous leaps that Columbo makes to catch his quarry, everything from a deaf man not hearing a running machine (“The Most Dangerous Match,” 1973) to teeth marks in chewing gum (“Agenda for Murder,” 1990).

To be clear, these lapses and leaps don’t really bother us viewers. For one, we know that Columbo has got the right man. Columbo almost always uses a “howcatchem” structure instead of “whodunnit” structure, spending the first act showing the murder. We know who the bad guy is and we want to see them get caught.

Well, sometimes we sympathize with the killer, as with the film star with dementia in “Forgotten Lady” (1975) or the sensitive wine connoisseur in “Any Old Port in the Storm” (1973). But in most cases, we have no sympathy for the rich and powerful who think they can do whatever we want, and thus take joy at their frustration when Columbo ambles into their house or gives a friendly wave from across the lawn. If their own consciences don’t plague them, then at least Columbo can annoy them.

Yet, Columbo’s status as a police officer means that he cannot represent “us” in the battle against the rich aka “them.” The first uniformed police departments in the United States — inaugurated in Boston (1838) and then in New York (1854) — came to be as a way of forcing the public to pay for the protection of the propertied classes and to force people into a work force. As scholar Mark Neocleous argues in his book A Critical Theory of Police Power,

Far from being the raison d’être of policing, “crime prevention” and “law enforcement” are far more important as rhetorical legitimations for the exercise of the state’s political administration of civil society, alibis for the police power. It is this that renders the police power a formless and all-pervasive presence in the life of civilized states … This all-pervasive presence manifests itself when the police power comes to intervene anywhere or any time there appears to be disorder or … for “security reasons,” even when those reasons are far from apparent to the rest of us.

Even modern attempts to “reform” the police fail to take account to the class warfare inherent in the institution. The police exist to enforce capitalist order.

It’s easy to see that ruling class consciousness at work when Joe Friday deals with some hippie on Dragnet or the muscle-heads on the current series S.W.A.T. fight anarchist terrorists. But Lieutenant Columbo doesn’t feel like a cop. So what is he?

Just One More Thing That Keeps Bothering Us

Columbo might be a product of network television, but he has surprisingly rich literary roots. Richard Levinson and William Link introduced a predecessor to Columbo in the short story “Dear Corpus Delicti,” published in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, which then became an episode of The Chevy Mystery Show called “Enough Rope.” The duo took inspiration in part from Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel Crime and Punishment, which features a police figure, but most relies upon the murderer’s conscience and sickness to crack the case.

Dostoyevsky sought to tell a story about the follies of arrogance and the inescapable grip of guilt and sin. Himself a one-time prisoner, Dostoyevsky certainly did not intend to praise the carceral system. Rather, he sought a greater justice, one not dependent upon police or prisons.

Much of the Dostoyevsky elements fell away as Levinson and Link revised the story into the stage play and then TV movie Prescription: Murder, the latter finally saw Falk become Columbo. Yet, one thing remained from the duo’s initial inspiration: the thirst for justice and the belief that a killer’s sins will find them out, no matter how much money and power they wield.

The remainder is what makes Columbo compelling television still today. We constantly see examples of the rich evading justice, shoring up power, and using their advantage to persecute others. Against all odds in real life, we have faith that justice can be done. And it’s all the sweeter when that justice comes via a man who has absolutely no interest in all the wealth-mongering that the evil doers covet.

As fundamental as those desires may be, pop culture cannot seem to separate the concept of justice from police. Police departments have long infiltrated media, especially film and television, in order to convince the public that safety and equality can only come through armed officers, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Columbo might be one of the clearest examples of this problem. We want to see someone take down rich jerks like Jarvis Goodland, and we want to see it done by the very type of person whom Jarvis disregards as insignificant, the type of person who takes time to care for the wellbeing of the wrongfully accused and laughs off the threats of the real killer.

“The Greenhouse Jungle,” like most episodes of Columbo, gives viewers the sense of justice we long to see. The fact that it comes through a copaganda lends doesn’t diminish the show. Instead, it only makes us long to see the actual downtrodden and neglected catch rich killers. That’s something worth telling not just our wives (or husbands and partners), but anyone who wants justice, unsullied by a policeman’s badge.